Before the calendars of elves began their counting. Before the elder forests learned their own arboreal language of wind and soil, there existed an age when the heavens and the earth were not separate but aligned in a single, perfect reality. Before the elder dawn, so distant that even the Orsolon tongues remember it only as an echo and a fragment, the great god of all dragons, later to be called Bahamut, who was then not yet known as the Platinum King. Then it was before when the vast and terrible wyrm-queen, later called Tiamat, became the Queen of Chromatic Ruin. They were instead the twin sovereigns of a united cosmos. Bahamut held dominion over the high firmament, where the stars wheeled in perfect measure. Tiamat ruled the deep bones of the world, where rivers of molten stone and the fertile violence began to call life itself into being. The celestial and the chthonic were not rival kingdoms but reflections of one another. They were lovers then.

Before the first birds sang, before beasts stirred in meadow or sea, before even the earliest forests stretched their green dominion across the newborn lands, the world of Dao Tyr existed in the long light of an endless sunrise. It was an age of hot wind and ash left by the world-forging strikes of unknown gods, when the mountains were still hot with the original fire and the seas had not yet learned the rhythm of lunar-locked tides. Storms wandered across the world like wrathful minds or elementals who quarreled over dominion. From that dust and from those wandering entities, the first elves found form.

The breath of the world gathered particles of light and memory, shaping them into beings who could see beauty where there had only been turbulence. Where wind touched stone and starlight touched soil, the first forms of the Raelfaen awakened. They rose not from womb or egg but from the quiet settling of harmony within chaos. Their bodies were slender as young branches, their senses keen as the hawk’s flight, and their minds carried an instinctive awareness of balance. They were the first people to walk the world with understanding rather than hunger. Where they stepped, the air grew calmer. Where they gathered, the wandering magic of creation learned to rest.

Yet the world they inherited was far from peaceful. Intrusive conquerors, insane and alien powers born from the turbulence of creation itself, dominated. Some were vast intelligences formed of storm and void. Others were creatures of writhing thought whose shapes defied memory once the eye looked away. They were not demons in the later sense, nor devils, nor beasts that might be slain by blade alone. They were remnants of a time before order, entities that had flourished in the chaos that preceded life. They moved through the world like fever dreams, warping land and sky wherever they lingered. When the Raelfaen first awakened, these older kingdoms regarded them as trespassers. The young elves could not yet match the power of such beings. They possessed grace and perception, but not the strength required to carve a place for themselves in a world still ruled by ancient madness. Many of the earliest settlements were swept away like footprints in the wind.

It was then that the dragons intervened. Bahamut and Tiamat still walked the world together in those days, and they beheld the young people of light and windwith a curious affection. The elves possessed an ability to shape beauty from uncertainty, which became something the dragons themselves admired. The dragons chose to aid and honor them. The six blades that had been forged in the First Crucible were not meant only for the quarrels of gods and wyrms. They were instruments through which order might be impressed upon a chaotic world. And so, in the earliest councils between dragon and elf, the blades were entrusted to the first champions of the Raelfaen.

The elves did not see them merely as weapons. They saw them as tools of shaping. With the Swords of Glory, they learned to protect the fragile clearings where life might take root. The Ivory Blade guided them in mercy and law, teaching them how to preserve harmony among their growing people. The Emerald Blade taught them how to defend the green shoots that had begun to rise from the soil. And the Crimson Blade burned with the will to confront the ancient horrors that still prowled the young world. With the Swords of Doom, whose darker power was not yet fully understood, the elves carved boundaries against the remnants of chaos. Rendpyre’s fierce dominion allowed them to drive back creatures that fed upon fear. Rendlereign gave them the cunning needed to bind dangerous powers beneath mountains and seas. Rendgray brought with it the cold strength required to end the existence of those ancient entities that could not be reasoned with.

The elves fought not as scattered tribes but as a single people. Their early wars were not against rival nations but against the lingering madness of creation itself. Battles were fought beneath skies that still glowed with raw magic, against enemies that twisted the shape of mountains or poisoned the dreams of entire valleys. It was during these ages of struggle that the first forests appeared. Where the elves prevailed, the land slowly calmed. The soil cooled. Rivers learned their courses. Seeds carried by wandering winds found places where they could endure. From these quiet sanctuaries rose the first great trees, and their roots anchored the world into stability. The spread of forests marked the first victory of life over chaos.

The Raelfaen stood beneath those trees as guardians of a fragile order they had helped create. Their cities were not yet towers of stone but living groves where magic flowed like sunlight through leaves. The swords passed from champion to champion, guiding the young civilization through centuries of peril. Even in those earliest ages, these powerful entities possessed voices, intentions, and desires of their own. Each blade believed it understood best how the world should be shaped. Each whispered its philosophy into the hearts of those who wielded it. And when the Sundering of Bahamut and Tiamat came at last, those whispers hardened into rival destinies. From that moment onward, the swords would no longer serve a single harmony. They would serve the great struggle between light and shadow that still defines the world’s fate. As the centuries unfolded, the differences between the dragon sovereigns deepened. Bahamut came to value law, guardianship, and the preservation of fragile life. Tiamat began to see the world as a thing that must kneel to strength. Compassion appeared to her as weakness, and patience as delay. Where Bahamut saw stewardship, she saw entitlement. The ancient chronicles say that Bahamut once approached her in the gardens of the First Mountains and begged her to abandon the path she had begun to walk. Let the world flourish, he told her. Let us protect what we have made. But Tiamat answered with a colder truth of her own. What we have made, she replied, belongs to the strong. The first betrayal was not a war, but a refusal.

It was then that Sardior, the Ruby Dragon and elder lord of equilibrium, descended from the crystalline vaults between the planes. Sardior was older than the quarrel itself, older perhaps than the first shaping of sky and soil. His scales burned with the deep crimson glow of star-born gems, and within his gaze lived the memory of a universe that had once known perfect proportion. He came in solemn authority. Where Bahamut embodied righteous law, and Tiamat embodied primal dominion, Sardior embodied balance. He was the quiet center between their opposing philosophies, the mind that understood that neither heaven nor earth could stand long without the other. From the high firmament, he called to them. His voice passed across the world like a chord struck in the bones of creation. “Beloved siblings of creation’s flame,” Sardior spoke, “the world you war over is still young. The creatures who walk it are fragile and newly awakened. If you tear the heavens in your anger, you will tear the world itself.” Bahamut listened. Tiamat did not.

Her wrath had already grown beyond reason, fed by centuries of resentment and ambition. To her, the plea of Sardior sounded like hesitation, and hesitation she despised above all things. Sardior descended between them then, his vast ruby wings casting a prism of scarlet light across the sky. For a moment, it seemed the conflict might yet be stilled. The younger dragons who watched from distant clouds held their breath. The first elves gathered beneath the new forests lifted their eyes in hope. But the fury that had awakened in Tiamat could no longer be turned aside. When Sardior spread his wings to separate the two sovereigns, her fivefold breath erupted. Lightning and acid, frost and poison, and flame struck outward in terrible union. Sardior deflected what he could, his ruby scales shattering the first waves of destruction into harmless sparks of magic. Yet the violence of her power tore open the sky itself. Bahamut rose to meet her.

Thus began the catastrophe remembered in all dragon lore as the Sundering of the Dragons. For seven days and seven nights, the heavens and the earth battled through them. The firmament cracked like a mirror beneath hammer blows. Mountains split under the force of their descent. Rivers turned from their courses as the air itself twisted under the violence of divine fire. At last, the Ruby Dragon withdrew in sorrow, never again to return to the world. He retreated beyond the firmament into the hidden crystalline realms where balance must sometimes wait until the world is ready to receive it again. Bahamut cast aside his blade and offered peace one final time, hoping that mercy might yet awaken the memory of their former unity. Tiamat answered with fire. Their clash tore the sky open.

When the struggle finally ended, their union had shattered, and the world itself had changed. Good and evil emerged as living forces within creation. Where once there had been only competing philosophies of power, there now existed moral gravity itself. Compassion and cruelty became distinct paths rather than shifting interpretations. And in the long shadow of that divine rupture, something new entered the world. From the scattered embers of dragonfire and from the broken fragments of Sardior’s attempted harmony arose the first generation of dragon lords who would later be remembered in the northern forests of Siluvaria.

They came to be known as the Scintilliant. Sixteen great wyrms emerged in that age, each carrying a fragment of the cosmic balance that had once united the dragon gods. Some bore the noble temper of Bahamut’s vision. Others carried the fierce independence of Tiamat’s legacy. A few embodied the neutral and contemplative wisdom that Sardior had sought to preserve. These dragon lords did not rule the heavens. Instead, they descended into the newly forming world. They claimed the forests, the mountains, the rivers, and the deep caverns of the North. Each carved out a dominion where their presence shaped the character of the land itself. Storms bent around their wings. Rivers changed course beneath their shadow. Entire ecosystems rose or withered depending on their temper. Thus, the Scintilliant became the living governors of Siluvaria’s vast wilderness. Some guarded the balance of life. Others hoarded power and knowledge. A few descended slowly toward cruelty and corruption as the centuries hardened their hearts.

Among them were names that would echo through the ages. There was Yropa, the Mountain Mother, whose amethyst wings sheltered the earliest elves of Silverymoon. There was Xyclodenes, the Eye of the Sun, whose golden fire kept the high peaks free from the creeping darkness of older realms. And there were darker figures as well, among them Orthmeck the Black, tyrant of poison marshes, and Angmehridon, the dreaming green lord of the deep forests.

The world had changed forever. The dragons were no longer unified. The swords they had forged would now awaken in a divided cosmos. And the young people of the world would learn that balance, once broken, is never easily restored. The six swords awoke fully to their own personalities and chose their allegiances. Three remained loyal to the vision of protection and justice that Bahamut had once defended. These came to be known as the Swords of Glory. Three others embraced the darker philosophy of dominion and ruin that had taken hold in Tiamat’s heart. These became the Swords of Doom.

Among the Swords of Glory, the first was the Ivory Blade, known in Kaeyenil as Aeltharion Valethis, which means the White Oath of Mercy. This sword possesses a calm and thoughtful spirit that values justice tempered by compassion. Its voice is said to be quiet and solemn, and it prefers to guide rulers and healers who place the protection of others above their own ambition. The presence of the Ivory Blade does not inspire fury in battle but instead brings clarity and moral resolve to those who carry it.

The second of the noble blades is the Emerald Blade, whose Kaeyenil name is Thalorien Sylvarae, meaning the Verdant Defender. This sword carries within it the living spirit of the forests and the wild world. It burns with anger at tyranny and corruption but is fiercely protective of the innocent and the natural harmony of the land. Through the ages, it has often appeared in the hands of wardens and rangers who defend the world’s green places.

The third blade of glory is the Crimson Blade, called in Kaeyenil Vaelorin Caethryn, which means the Red Justice. This sword embodies righteous wrath. It burns with the desire to destroy evil wherever it finds it. Yet this same passion places it in constant tension with the boundary between justice and vengeance. Among the Swords of Glory, it is considered the most dangerous because it urges decisive action and does not easily tolerate hesitation in the face of cruelty.

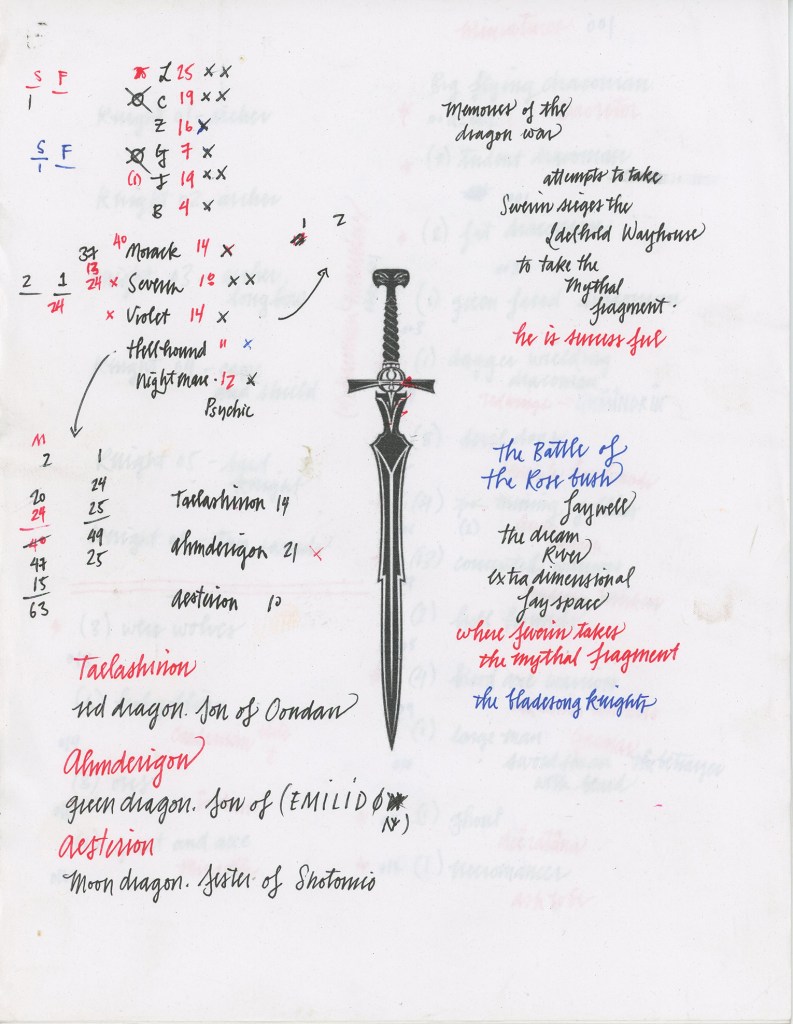

Opposed to these stand the three Swords of Doom, each shaped by the darker philosophy that emerged from Tiamat’s rebellion. The first of these is Rendpyre, known in the corrupted tongue of Aidriffon as Rendpyre Vaerath, which means the Flame of Dominion. This blade exults in conquest and feeds upon ambition. It whispers promises of empire and glory into the minds of those who wield it, urging them toward rule through fear and domination. Many tyrants of history have been guided by its seductive voice.

The second is Rendlereign, whose ancient name is Rendlereign Dathryss, meaning the Sovereign of Ruin. Unlike its fiery sibling, this sword is patient and calculating. It delights not in chaos but in control, guiding kings and rulers toward cruel but efficient forms of power. Its influence spreads quietly through courts and councils until entire kingdoms fall under its shadow.

The third and bleakest blade is Rendgray, called in Aidriffon Rendgray Maltheris, meaning the Shadow of Ending. This sword does not crave conquest or glory. Instead, it embodies entropy and despair. Those who carry it find their hope slowly eroded until they become instruments of decay. Wherever Rendgray travels, courage weakens, and civilizations falter.

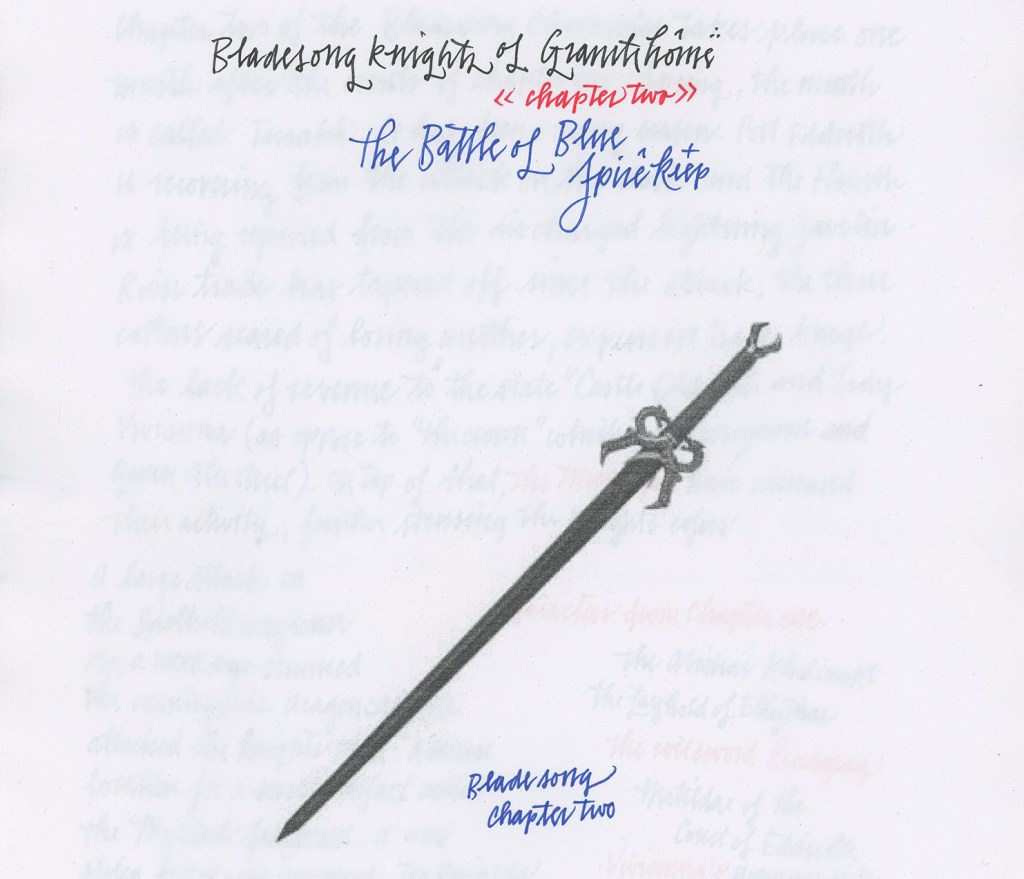

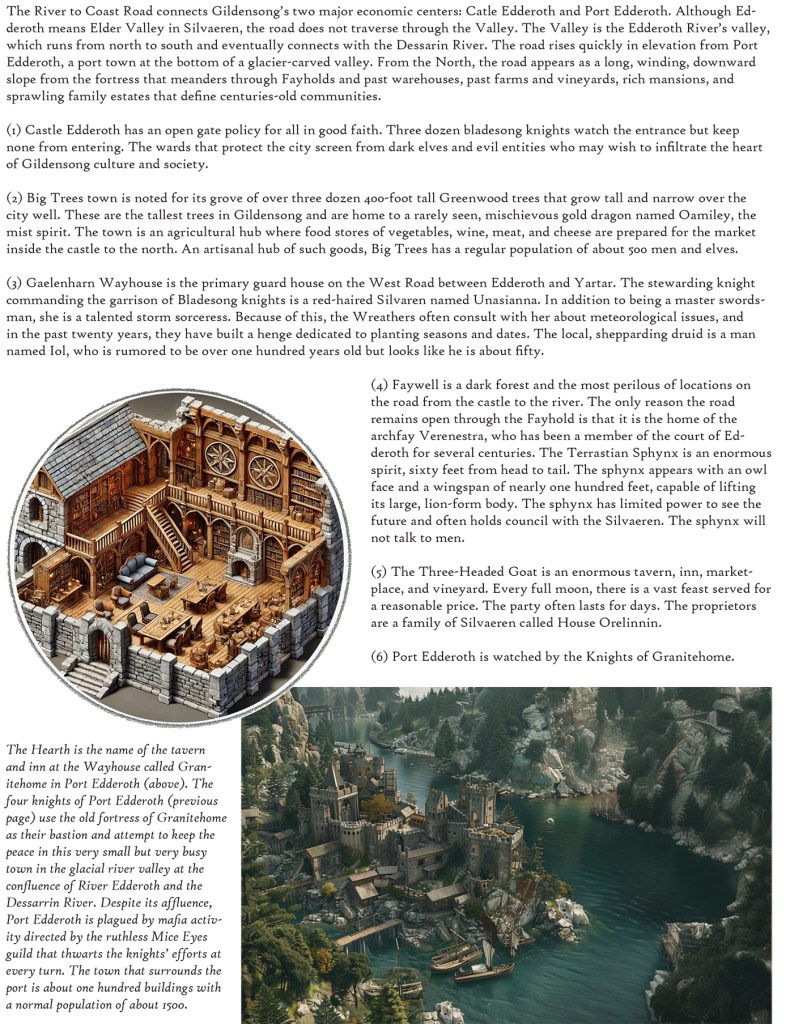

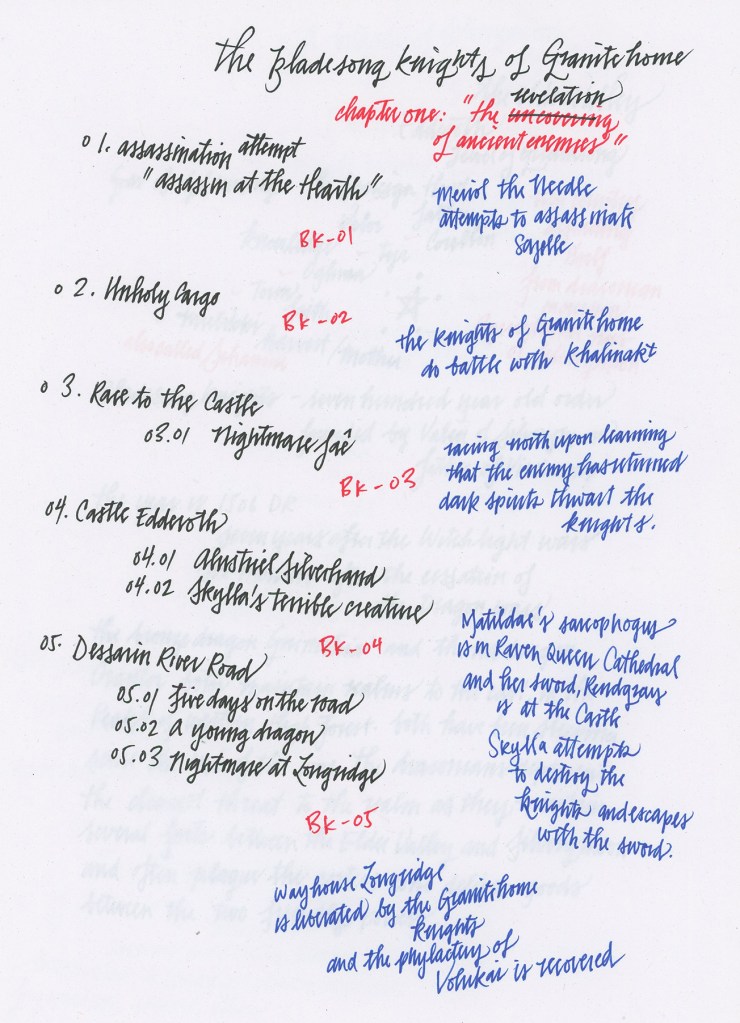

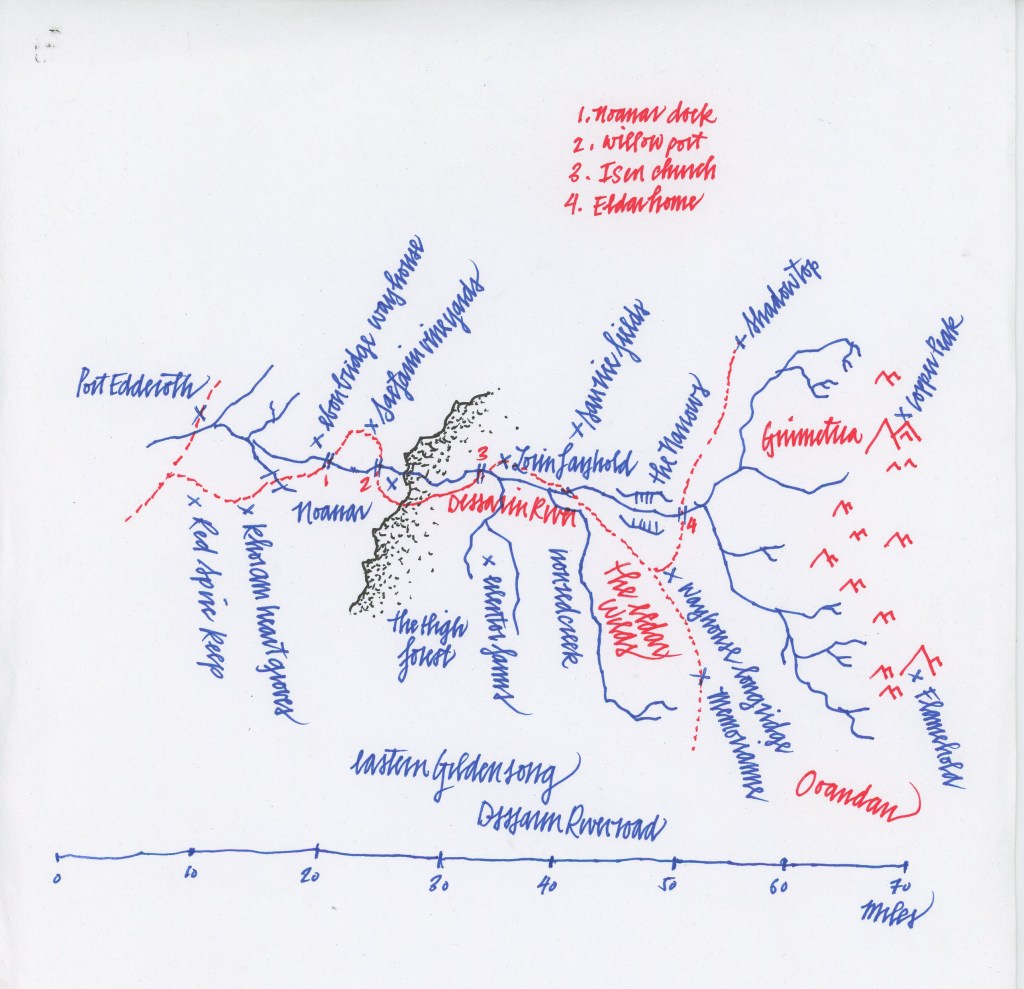

Across the ages, these six swords have known some wielders who became legends, whose names are still sung in halls of honor. Others became monsters whose memory is spoken only in warning. The blades themselves remember everything. They remember the love that forged them and the betrayal that divided them. They remember the first war between heaven and earth. And they wait. In the present year, 1509 by the calendar of men, only one of the Swords of Glory is known to walk openly in the world. The Crimson Blade rests in the hand of Prince Springfield Ethuliaer of Silverymoon, knight of the Argent Legion. Two of the Swords of Doom are accounted for. Rendlereign lies sealed within the deep vaults of Castle Edderoth, where ancient wards and careful watchers keep its whispering voice contained. Rendgray sleeps beneath the granite halls of Granitehome in the harbor fortress of Port Edderoth, guarded by dwarven keepers who know only that it must never again see open sky. The final blade of doom, Rendpyre, remains lost to history. The six swords were never meant to remain apart. Should they ever be gathered again in one place, the ancient wound between heaven and earth may open once more.